I know that one of the big draws to sourdough fermentation of whole wheat is the reduction of phytic acid.

Sprouting (malting) also reduces phytic acid, but causes other issues like gummy crumb.

I was recently reading about 100% sprouted wheat recipes that eliminated any preferment. Fermented warm and fast, shaped and cooked.

The author claimed that by keeping the ferment warm and fast it allowed the yeast to do its job before the enzymes and sugars in the malt had a chance to ruin the crumb.

I was thinking that this might make a good Community Bake, once we are done with the 50% rye.

I'd like to get a link to the 100% malted wheat recipes please.

https://brodandtaylor.com/blogs/recipes/how-to-bake-with-sprouted-wheat-flour

I would not call that malted. Yes, I have used the Lindley Mills "Super Sprout". Good stuff.

While I know that this has been discussed here before:

https://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/38521/malt-powder-or-sprouted-flour

But the Bakerpedia makes no distinction:

https://bakerpedia.com/processes/sprouting/

Though they do mention that the quality of the malted flour is measured using the "falling number test" which could (would?) most likely be affected by sprouting time.

Here is another reference. They claim the difference is that Malting occurs when the sprouted grain is dried.

http://www.nzdl.org/cgi-bin/library?e=d-00000-00---off-0fnl2.2--00-0----0-10-0---0---0direct-10---4-------0-1l--11-en-50---20-about---00-0-1-00…

Which author and which book? I have never heard of this.

Reinhart has a book on baking bread, pizza, foccacia, bagels, pancakes, crackers, muffins with sprouted flour. Also has some recipes for sprouted GF flours. Current kindle price is $9. I've seen it as low as $5.

https://www.amazon.com/Bread-Revolution-World-Class-Sprouted-Techniques-ebook/dp/B00JYWW486

The sprouted "pulp" formulas look interesting too.

Fortunately, you can see the recipes in the Table of Contents, in the online free sample, click "Look Inside."

Now I have yet another book to put on my wish list.

I have several of Reinhart's books. Once you read the first recipe, it's pretty much cut and paste after that with changing ingredients. His take was pretty much what I outlined in my original post, but added high hydration and folds.

I believe there is a subtle difference between sprouting and malting. In both cases the kernel is sprouted, but malt is allowed to sprout for a longer period of time until the sprout is the length of the grain. I believe the baking characteristics are different for each.

Sprouting is the process of germinating the grain, malting is what you do with the sprouted grain.

I believe the confusion arises because malt also has been sprouted just like sprouted wheat flour. However, sprouted wheat flour will stop the sprouting after ≈1 day, too short to significantly increase the α-amylase activity. Both sprouted wheat or malt have to be dried to be ground into flour or stored for the brewer. The maltster can also impart additional flavor elements in the malt by kilning for longer periods and/or higher temperatures. If the malt is toasted long enough it will lose its diastatic power and can only be used as an flavor/color adjunct in brewing.

I found some references that allow correlation of diastatic power (DP) of sprouted wheat flour with wheat malt and other malt. Part of the difficulty in comparing them is that malt is dominated by the brewing industry that traditionally used °Lintner or °Windisch-Kolbach to measure DP. I am not as familiar with the baking/milling analytical methods, but it seems falling number or other methods are used for DP.

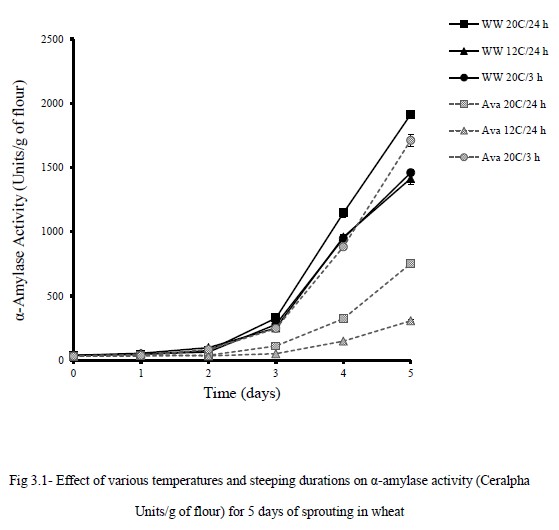

However, I found studies that use another α-amylase method reported as Ceralpha units. One reference is for brewing malts with high DP and two others for sprouted flours. A typical wheat malt has a Ceralpha value of 95 U/g.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jib.665

Wheat flour Ceralpha is typically <1 U/g. Sprouted flour has a higher Ceralpha value and lower falling number, but it is still low compared to malt.

https://scholarworks.montana.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1/16179/bummer-johnston-controlled-2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Allowing the wheat to continue sprouting results in a rapid increase of α-amylase activity.

https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10214/6672/Shafqat_Saba_201305_Msc.pdf?sequence=1

The sprouted flours that are commercially available I believe have low α-amylase activity. Otherwise, they would be unusable for bread baking in any quantity. I have baked bread with the King Arthur Sprouted Wheat flour (from Lindley Mills) and it did not display any gumminess.

So, the longer (up to a point, I am sure) you sprout the grain, the better your malt is for brewing.

I understand why there would be a benefit to differentiating between malts for brewing an baking additives vs less sprouted malts intended for baking. So, if we want to split that hair with the terms sprouted for one and malted for the other it seems like a viable solution since the duration of the sprout can affect the qualities of the malt in profound ways according to the duration and processes used to malt the sprouted grains.

I’ll look again, but don’t remember seeing a definition of root length differentiating sprouted vs malted (using the above definitions of both). Your tables listed times, and after one day sprouts are barely ( I’d like to say not) visible. vs 2 or 3 days where they can be as long as the grain (depending on temperature).

I think once we have nailed down the terms this would make an interesting community bake, we could even explore the limits of sprouting times vs bread quality. A bare minimum would need (I believe) to be a 12 hour soak to get the benefit of reducing physic acid.

I believe the root length and duration of sprouting is similar to bread timings. Temperature can affect the rate of sprouting, so root length becomes a valuable visual cue.

Here is a description of the malting process from Briess Malt:

https://www.brewingwithbriess.com/malting-101/malting-process/

Phytates aren't all bad. Debra Wink commented on this in a previous thread:

https://www.thefreshloaf.com/comment/507610#comment-507610

There may be anti-cancer properties in the phytates. Here is just one reference:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01635589309514232

I have included a reference at the bottom of my post. This is an excerpt of the pertinent facts, including both positive and negative information. Your second link is a theory based on inference, hardly compelling.

Phytic acid prevents the absorption of iron, zinc, and calcium and may promote mineral deficiencies ( 1 ). That's why it is often referred to as an anti-nutrient.

Phytates also possess antioxidant properties. These properties have led researchers to explore their protective potential against diseases such as heart disease and cancer. [6]

For example, researchers believe that phytic acid may be used therapeutically for the treatment of colon cancer and other cancers. But more studies need to be done to prove safety and effectiveness. [7]

The chelating process by which phytates bond to iron and toxic minerals and removes them from the body has led to theories about their use for detoxification. Currently, phytic acid is used therapeutically to remove uranium. [8]

However, the same ability that makes phytates able to remove uranian or iron from certain cancer cells, also depletes essential minerals from, and harms non-cancerous cells.

Phytic Acid Risks: Impaired Mineral Absorption

Once ingested, phytic acid forms insoluble compounds with minerals, proteins, enzymes, and starches. This impairs the absorption of proteins and minerals such as iron, zinc, calcium, and magnesium. [15]

Deficiencies in these minerals can result in health problems including:

Phytic acid is not a major health concern for people eating a nutrient dense diet. But if you have higher nutritional requirements, inadequate intake, or deficiencies of minerals and trace elements, you should limit phytic acid foods. [31]

The average phytate intake in the U.S. and the U.K. is between 631 and 800 mg per day. In Finland, it’s 370 mg. It is 219 mg in Italy and only 180 mg in Sweden. [37] Most likely much higher among board members that don't use sourdough since the average American doesn't eat that much whole grain.

400-800 mg per day may be safe.

For people with bone loss, mineral deficiencies, and tooth decay, we advise less than 400 mg. For children and pregnant women, it’s best to reduce phytic acid as much as possible.

there are studies exploring the positive roles of phytic acid. These revolve around its antioxidant properties and its ability to bind with other minerals. The later function suggests that it may be used to target certain cancer cells that need iron.

But for most people, the ingestion of phytic acid is a net negative. It reduces the absorption of iron, zinc, calcium, and magnesium. And in extreme cases, eating too many phytic acid foods can cause nutritional deficiencies.

Reference: https://www.doctorkiltz.com/phytic-acid/