Thank you, David, for the title (AKA the little SD starter that could); it really was a long series of events! It began Friday night when I was trying again to finish part one of Little Dorrit, but, alas, I fell asleep again. When I awoke, with my neck aching, I stumbled into the kitchen and began throwing together the levain for Leader's sourdough rye loaves. Earlier in the day I had calculated that I needed to get this going just before bed if I wanted to bake the loaves the following day. When the levain was accomplished, I stashed it in the water heater closet, which maintains a nightly temperature of about 73º F, for overnight fermentation.

At about 9 AM the next morning I pulled the levain and from its incubator and began mixing the dough. By 9:30 AM with the flour and water hydrated and the levain and salt mixed, I began the machine knead, which needed a lot of manual help in my 1976 KA--there was much stopping and starting, and repositioning, wet bowl scraper in hand, until the battle of woman over machine was won, and dough decided it would after all sit on the "C" hook. Leader said to knead on "2" for a minutes and then on "4" for 8 to 9 minutes, but at about 6 minutes in on speed "4" the dough that had been behaving nicely all of a sudden melted off the hook and lay in the bottom of the bowl, so I decided it was probably kneaded enough. I stopped the machine, scraped it into the proofing bowl and let it rest for an hour.

10:45 AM: After performing one stretch and fold on the dough and being pleased with its structure, I returned the nice little ball to its proofing bowl, stashed in back in the water heater closet and set my timer for 3 hours.

1:45 PM: After checking on its progress, or in my case lack of progress, over the course of the previous hour I began to get a little worried. Which starter had I used last night, the weaker bread flour or the stronger whole wheat flour one? I couldn't recall exactly. I had meant to use the whole wheat flour starter, but doubt was setting in. And, there were also considerations about the cheese. I had made a special trip to acquire the precise cheese needed, bleu d'Auvergne, on Friday and didn't want to waste it on something that might be a flop. What does a person do in these circumstances? Put a cry for help out on TFL and make soup. I posted my cry, and started two pots of soup: the lentils with smoky ham that I had especially selected for dinner as a perfect foil for my little loaves and an old stand-by, chicken stock.

Four hours past, then five. Somewhere between the four and five hour mark I thought that I might be seeing signs of growth but it was painfully slow and who knew if or for how long it would continue. Still I held out hope and prepared the cheese, just in case.

At six hours, soups simmering away, I checked again and saw definite growth. Would it continue? I just didn't know but said "patience" to myself and tried to keep busy. Jim was now watching March Madness, even though it is April, drinking Orangina and vodka, and calling me "Marge". I wasn't amused and told him to make his own drink if he wanted another!

I served the soup somewhat disappointedly with Vermont Sourdough.

Somewhere between seven and eight hours, I checked on the dough's progress and determined it had, indeed, probably doubled. I decided to risk the price of the cheese and complete the loaves. All rolled up and nestled in little bread pans also especially acquired for this bread, I returned them to the water heater closet.

After another painful hour I positioned the racks, placed a cast iron skillet in the lowest position, and on turned on the oven. I also checked on the loaves. Much to my amazement, they were rising in their tiny pans. My worry was fast turning around: I concluded there was reasonable cause for success.

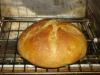

An hour later, I loaded the ice-cubes in the hot skillet and bread pans in the oven. I looked through the window after 10 minutes and was positively elated to see a lot of oven spring.

I removed my lovely little, bubbly and fragrant parcels after 35 minutes. The entire house smelled divine (no doubt the chicken stock that was still simmering also aided the ambience of the evening).

Another 45 minutes past, and there was just 15 minutes more to go of part one of Little Dorrit, but I couldn't wait any longer. I sliced into one loaf, ate several pieces with gusto and we retired, I feeling very victorious and the chicken soup still simmering. It was pleasant dreams here for all. I awoke at 4 AM, turned off the soup and returned to dream of breakfast for a few more hours.

--Pamela